February 16, 2005

The History of the Indian Rope Trick

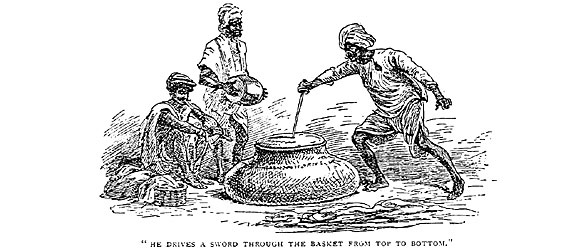

Fascinating story about the history of a legendary bit of street magic. This is a book review at the NY Times by Teller of Penn and Teller. Hat tip BoingBoing bq. 'The Rise of the Indian Rope Trick': The Grift of the Magi When John Elbert Wilkie died in 1934, he was remembered for his 14 years as a controversial director of the Secret Service, during which he acquired a reputation for forgery and skullduggery, and for masterly manipulation of the press. But not a single obituary cited his greatest contribution to the world: Wilkie was the inventor of the legendary Indian Rope Trick. Not the actual feat, of course; it does not and never did exist. In 1890, Wilkie, a young reporter for The Chicago Tribune, fabricated the legend that the world has embraced from that day to this as an ancient feat of Indian street magic. bq. How did a silly newspaper hoax become a lasting icon of mystery? The answer, Peter Lamont tells us in his wry and thoughtful ''Rise of the Indian Rope Trick,'' is that Wilkie's article appeared at the perfect moment to feed the needs and prejudices of modern Western culture. India was the jewel of the British Empire, and to justify colonial rule, the British had convinced themselves the conquered were superstitious savages who needed white men's guidance in the form of exploitation, conversion and death. The prime symbol of Indian benightedness was the fakir, whose childish tricks -- as the British imagined -- frightened his ignorant countrymen but could never fool a Westerner. bq. When you're certain you cannot be fooled, you become easy to fool. Indian street magicians have a repertory of earthy, violent tricks designed for performance outdoors -- very different from polite Victorian parlor and stage magic. So when well-fed British conquerors saw a starving fakir do a trick they couldn't fathom, they reasoned thus: We know the natives are too primitive to fool us; therefore, what we are witnessing must be genuine magic. And the trick itself: bq. In 1890 The Chicago Tribune was competing in a cutthroat newspaper market by publishing sensational fiction as fact. The Rope Trick -- as Lamont's detective work reveals -- was one of those fictions. The trick made its debut on Aug. 8, 1890, on the front page of The Tribune's second section. An anonymous, illustrated article told of two Yale graduates, an artist and a photographer, on a visit to India. They saw a street fakir, who took out a ball of gray twine, held the loose end in his teeth and tossed the ball upwards where it unrolled until the other end was out of sight. A small boy, ''about 6 years old,'' then climbed the twine and, when he was 30 or 40 feet in the air, vanished. The artist made a sketch of the event. The photographer took snapshots. When the photos were developed, they showed no twine, no boy, just the fakir sitting on the ground. ''Mr. Fakir had simply hypnotized the entire crowd, but he couldn't hypnotize the camera,'' the writer concluded. bq. The story's genius is that it allows a reader to wallow in Oriental mystery while maintaining the pose of modernity. Hypnotism was to the Victorians what energy is to the New Age: a catchall explanation for crackpot beliefs. By describing a thrilling, romantic, gravity-defying miracle, then discrediting it as the result of hypnotism -- something equally cryptic, but with a Western, scientific ring -- The Tribune allowed its readers to have their mystery and debunk it, too. Newspapers all over the United States and Britain picked up the item, and it was translated into nearly every European language.

Comments

Post a comment